Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

@2dark2sinister is an Instagram page run by Jack Shepherd. On the page, Jack documents the darkest Tech-Step, Neuro-Funk, and Jump-Up Drum ‘n’ Bass from the years 1995–2002. Jack’s page is one of a number of pages documenting the long and complex history of Jungle Drum ‘n’ Bass. I thought I’d chat to Jack to find out about the push on social media to document rave history.

Quite a few people seem to be curating their own niche within Instagram, documenting aspects of Jungle Drum ‘n’ Bass and Dance music history more broadly. What made you want to start 2Dark2Sinister?

Jack: I started @2dark2sinister as a place to showcase what I was buying after seeing other accounts, namely Kriminal Archive, doing something similar early on into my journey into the sound. At that point I was spending like six hours a day sifting through Discogs looking for tunes and honestly just wanted to show the rewards from that graft.

How long have you been collecting records? And has it always been Tech-step/Neuro-Funk/Darker 1996-2002 sorts of tunes?

Jack: I’ve been collecting records since around the end of 2021. Up until last year, I was purely buying 1997-2001 drum & bass, until I started getting really into Happy Hardcore after hearing a lot of my Dad’s stories of raving when he was around my age.

When people reminisce about Jungle and Drum ‘n’ Bass and document it, particularly on Instagram, it’s typically a very specific sound—either ’94–’96 intelligent or atmospheric productions, or that ’94 Ragga sound. What is it about the tunes you post that you feel makes it important to share and document them?

Jack: I think it’s so important for me to share the tunes I do, as not many others do. Whether that sound isn’t as sexy in comparison to the more commercial appealing Jungle & the intelligent sound, if that makes sense. A lot of the tunes I post are ones from sets I’ve heard from pirate radio sets from Rude FM or Cyndicut – a setting people glorify but it is nowhere near as much about the music getting played on those stations.

Obviously, with Happy Hardcore as well, it has experienced that similar sort of derisory attitude that a lot of Jungle and Drum ‘n’ Bass fans have had towards Tech-step, darker Jump-up and early 2000s Drum ‘n’ Bass. A lot of criticisms, I think wrongly, are thrown at the two as being “too in your face” and “not as sophisticated”.

Jack: See, on the “too in your face” criticism, to me that is fair, but also, that’s what I love about it. I just love those tunes, like Powder – Tirant, which purely exist to be lairy. Tech-step, though, is just as technical as Jungle in my opinion.

Touching on my Dad raving in the ‘90s, I do think there is a potential interesting link there, as it wasn’t something I consciously thought about when I got into that late ‘90s sound. I do think it’s a strange that that’s what I was so drawn to – obviously a completely different genre but very interesting to think about. We’re from Portsmouth, which was very deeply involved in the Happy Hardcore scene of the ‘90s, with a lot of the biggest names being from Portsmouth (Fusion & Hectic Records, as well as

Hixxy being born here) and its surrounding areas.

With Tech-Step, there is quite an aesthetic jump from ‘93-‘95 Jungle, with a greater emphasis on technological warfare, computers, robotics, artificial intelligence, etc. It seems particularly relevant still, which is great, I think.

Jack: I didn’t even think about that – yes, true, it goes very dystopian up until the turn of the millennium. Then, post-2000, it goes all sci-fi, space-age, and it’s lost that same sinister edge to it.

What’s been your biggest bargain? And do you have tunes you wish got more love?

Jack: The biggest bargain I remember picking up was Code Of The Streets – The Trouble on vinyl compilation for £4 on eBay. It has the Energise VIP on it, which I’ve heard being battered a lot by most DJs in the darkside space. It’s a proper classic. As for tunes I’ve got that don’t receive the love they deserve, I’d say the Chel series by DJ Phantasy. They were all white label releases around ’99, but especially Chel 002 & 003 . 002 has a proper rolling bassline with some serious weight to it (the video on the page really doesn’t do it justice). Definitely one I’d love to hear an MC on, whereas 003 has this ridiculous alien-sounding bassline and some heavy breaks.

As a dance music archivist, are there any other Instagram pages you’re a fan of?

Jack: As for accounts I love, I could honestly chat for ages bigging up people, but I’ll keep it short – Kriminal Archive, DJ KRPT (@djkrptdnb), and I recently found Pablo G (@pablo_g_vinyl_videos) too. All these accounts are so consistent with what they do. As for non-Drum & bass, I am a massive fan of @onefourtybpm and his write ups. For sure something I aspire to do on my page. Favourite Child (@fav0uritechild) is also great for the same reason – big ups to her. And one to watch out for would be @1051records. I know Ellis is going to be posting a lot of good tunes over there, as well as some pending new music – focusing on the drum and bass sound that I love.

Many of the accounts documenting dance music history seem to be run by relatively young people, including yourself. Why do you think that is? Beyond a general interest in the music, do you think there’s also a sense of nostalgia for something that our generation has missed out on?

Jack: Oh, 1000%, I agree there is definitely a sense of nostalgia for something we all missed out on, but that’s massively coupled with the music back then being miles better sonically. I know for me, I got into the old-school sound initially through collectives like Singularity and Da Demolition Squad (specifically Ariel @bringingbackdasound),who pushed out good-sounding music alongside information about how the ’90s and early ’00s were a much better for music and atmosphere. That definitely solidified the nostalgia for me. Then, speaking to my Dad later about his own experiences just honestly made me jealous, but I’m glad I can somewhat share experiences with him about that.

Do you have any plans for the page going forward? Is there anything you’d like

to explore or do with the music that you haven’t done yet?

Jack: As for plans, I have so many plans for the page. I need to learn to be more consistent on there, but I’d absolutely love to do a few different series. For example, going record shopping in different cities with a different guest in each place, as well as doing a series similar to one that Locked On Records does, where DJs come on and select a few of their favourite plates and speak on them. I’d love to do that with

darkside, as it’s very similar to what I do already, just getting another person’s taste and perspective. Obviously, I’d love to learn to mix properly, as my collection is rather

good – even if it’s just for me.

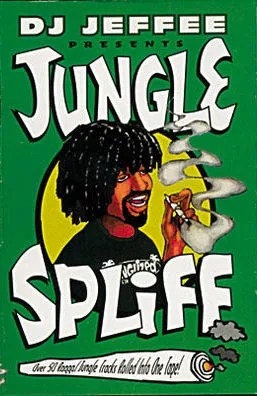

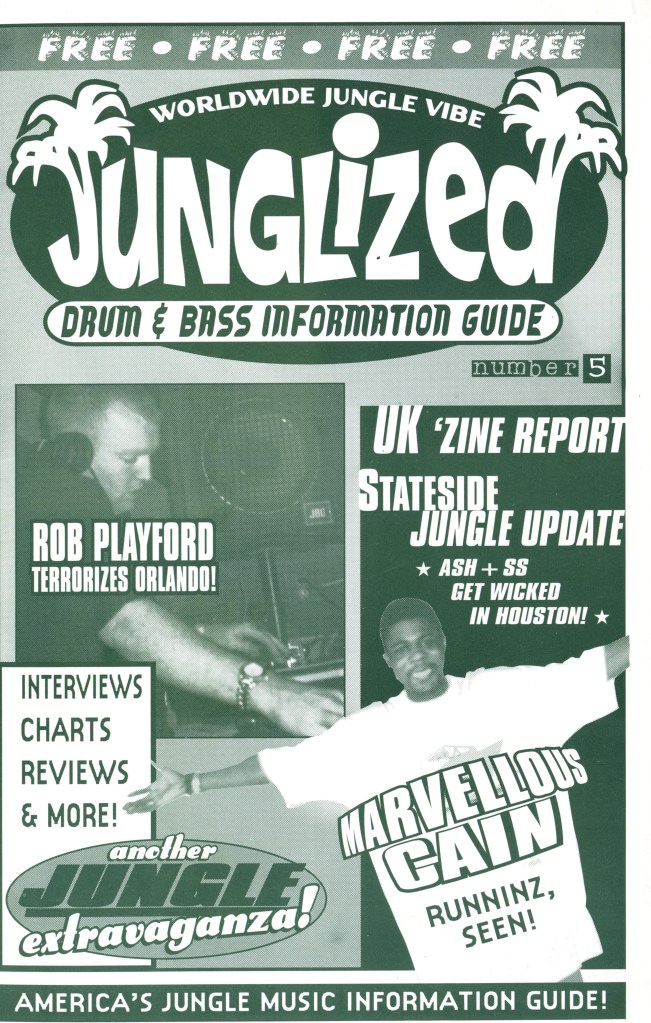

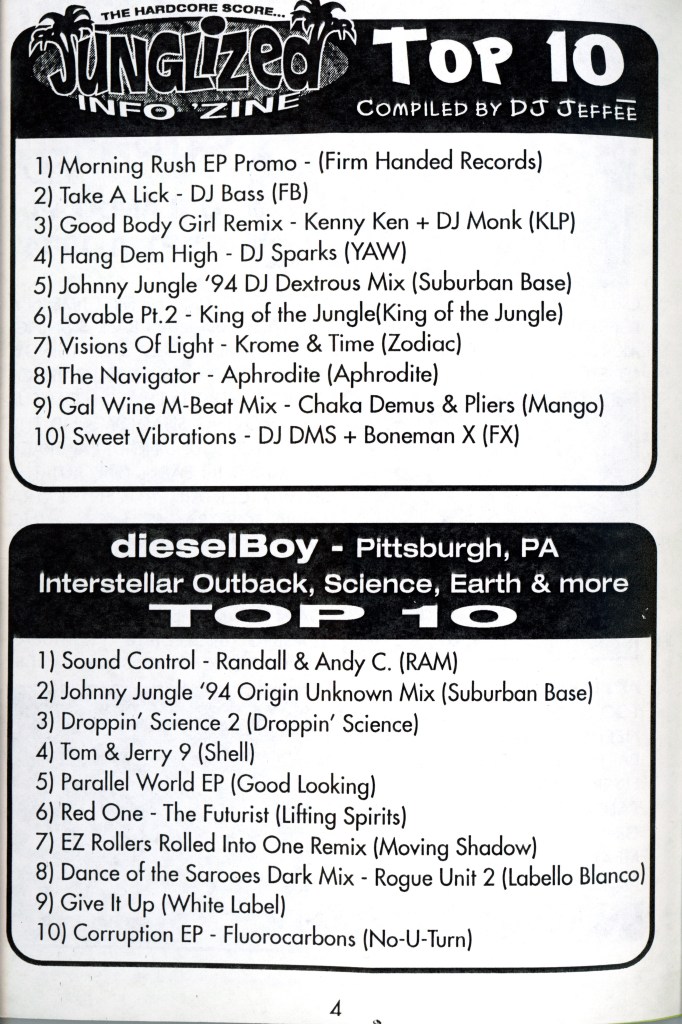

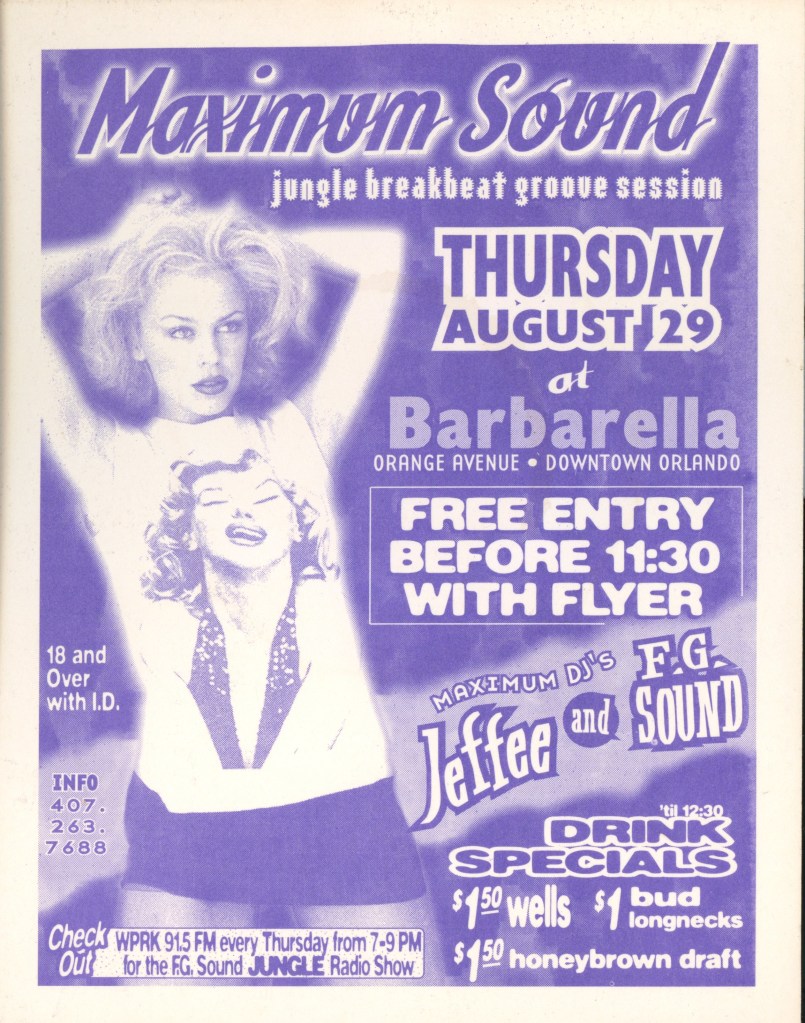

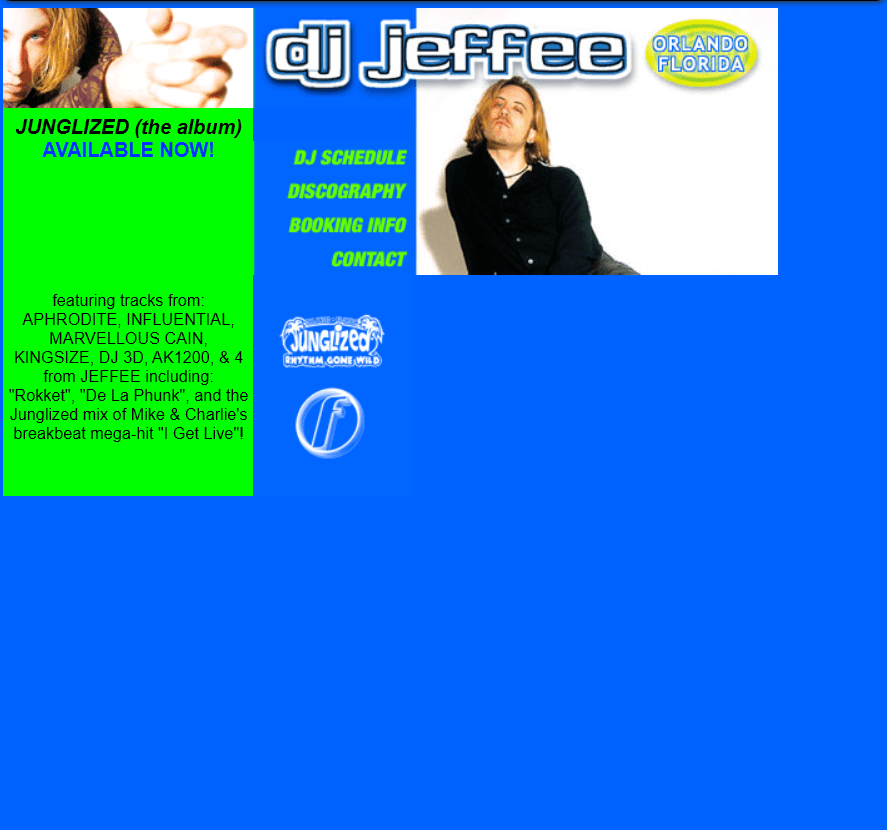

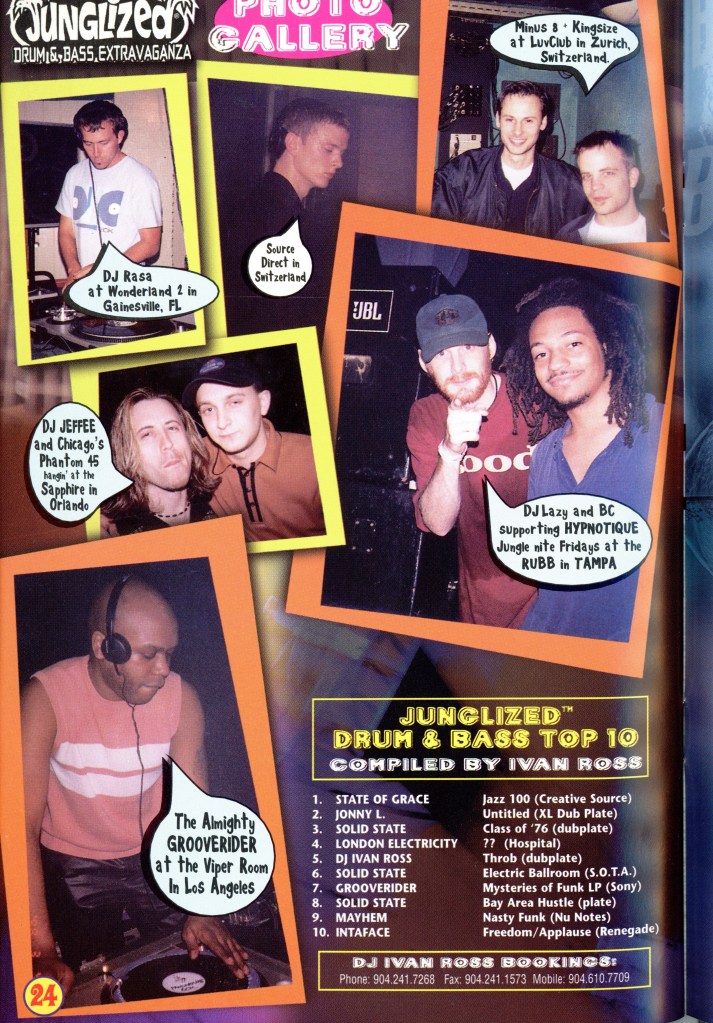

I conducted this interview with Jeffee last summer. For a brief bit of context, Jeffee was probably the preeminent US Junglist of the 1990s. Today, people likely know him for his Jungle Spliff tape, which was uploaded to YouTube a number of years ago and has since acquired somewhat of a cult following (Jungle Spliff by DJ Jeffee (DJ Mix, Ragga Jungle): Reviews, Ratings, Credits, Song list – Rate Your Music).

However, in the mid-1990s, Jeffee was pivotal in connecting the US scene with his fanzine Junglized. Along with C.H.A (Chicago Hardcore Authority), Jeffee helped lay the foundations of the scene that still exists today.

In speaking to Jeffee, I hoped to cover everything one would want to know about this legendary figure, whilst also addressing broader topics that seemed pertinent to his experiences within the scene, such as the influence of the Internet and zine culture. Junglized emerged within a fascinating juncture in history, as print media found itself at odds with the rise of the Internet and web culture. I wanted to chat to him to understand his take on these events ,but also, because there isn’t much info about the man out there. Anyway, as you shall hopefully see, Jeffee is a wonderful dude. He can be found today making some wonderful Dream Pop under the name Shampoo Tears (https://soundcloud.com/shampootears).

How did you get into the music in the first place?

Jeffee: I moved to Florida in 1994, but before that, I had come from Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh is very close to a town called Cleveland. One time in Cleveland, around 1990, a guy named Mike Philly did a ‘Manchester’ night in this club where you had to ride this cool freight elevator to get up there. I was on the elevator for another occasion, and he was there – he had an Adamski record, and I said something about Adamski. He responds, “That’s cool… I do this night… and I also help my other friend, Rob Sherwood. I DJ for him sometimes when he takes a break”. I went to one of these events once, and he had all these early Reinforced records, Manix, and stuff like that. I heard that and went, “holy hell, that’s different from what I’ve been listening to,” and got into it there.

This Sherwood guy also said, “Since I’m a DJ, I’m on this record list, and I can get all these records that come over from the UK. If you want any of these things, just give me some money, and I’ll get them on the next delivery”, so I started doing that. And then I got these two old Numark turntables and started learning how to DJ. I just fell in love with it from there. Soon it was Production house. Suburban Base, too. With these turntables, back then, you could mix any kind of stuff around; you could mix a house record with a breakbeat record – there were no categories, really. It was just all ‘techno’. So, I got enough records together. My first gig was in Pittsburgh at this pool hall after it had closed, and everybody was dancing between the pool table, but I played the set and thought it was terrible. But everybody thought it was great, so I said “I’m gonna go home and practice even harder”, and man, it just took off.

What made you want to move to Florida?

JEFFEE: Well, I had heard of this guy… Somebody I knew went on tour with the Prodigy, and he brought back a tape of this guy called AK1200 down in Florida. This guy scratches and stuff like that, but he’s playing the same things we are. I had never thought of moving to Orlando; this is ’93. And then, I moved to Orlando in ’94. When I moved down here, I thought because AK was here, it was a Jungle mecca of some kind… nope, it was breakbeat, but Florida breaks only go so fast, and then they stop. That early Rachel Wallace Suburban Base kind of speed, and they never went any faster.

I thought I was going to make the most of this. And so, I took my tape into a local record store, and the tape had a fully printed cover, as I had always worked in Graphic design and print shops. It was special; it was a full-colour print, and everyone else’s was TDk90 handwritten or whatever. That’s where AK got my number.

What made you want to start Junglized?

JEFFEE: Well, I took the money from when I had moved… I had a 401k, the thing where they save money for your retirement, and I bought a Macintosh with it. I said, “I’m going to make a magazine”, like a fanzine, because we keep hearing of all these artists across the country. I had heard of a guy out in New Mexico playing Breakbeat Jungle, a guy in Los Angeles, and a guy in Toronto called Ruffneck. He [Ruffneck] would play all these M-Beat records +45, all the way, as fast as possible… I really liked that stuff.

But also, when I was up in Pittsburgh and Cleveland, you had to order a pizza to find out the location of a rave. When I got down here, raves were advertised on the radio. It was all commercial down here already. It was definitely a fight to get a gig, and that’s sort of why I started Junglized. The first issue of Junglized is basically all about Florida. It was tough, but that magazine helped me… people started recognizing me, and AK even wrote a couple record reviews.

AK also worked at Airborne Express – an early FedEx that went out of business – and he could ship out the magazines for free. I would get them printed, type ’em out, and ship him boxes and boxes of them. He would get all the addresses to the UK record stores and all the American record stores, and we shipped them out for free. That was good distribution for us, so people were always calling us like… “Can I run an ad?”…. “I can give you a scene report.”

Before this, I was a punk rock kid in high school; I wrote scene reports in Pittsburgh for all the punk bands and crap when I was 14, 15, and 16. And then I went through a psychedelic phase, and by ’88, ’89, Acid House came out, and I said, “well, I’m listening to all this psychedelic stuff from ’67”, and I saw how Acid House tied this together. When I heard the wobwobwobwob, I was like, “I’m buying into it”. That helped a lot in getting me into the music… but also in making me want to start Junglized.

At that time, how closely were you able to follow the scene in the UK?

JEFFEE: It always came from England, but we [the US scene] were close right there. Shut Up ‘n’ Dance… we had those records and played them pretty much at the same time. But it was a case that some people would love them, and others would be like, “Ehhhhhh, what the hell was that?!?!”.

Around 1995, AK even got in touch with Dan Donelly from Suburban Base and suggested that they should come over to Florida… Dan wanted to bring the whole crew out to the US anyway. Dan said, “Can you just set up a rave for us?”. We did it at this Metro Skating Rink and called the event Junglized.

When Dan Donnely came over, was that the first-time you had met someone from the UK scene?

JEFFEE: Yeah, it was. But we really struck it off good with Marvellous Cain. Marvin used to come all the time, and we used to get him shows in Florida because he’d want to go shopping all the time, but he is another way I got promos and stuff. By ‘97, all those guys wanted to come over here so badly. I think Nautica and Tommy Hilfiger cost a lot of money over in the UK, so I would go to the mall here and buy a bunch of Tommy Hilfiger, I’d ask them what size they were – everything was oversized – and then they’d ship me boxes and boxes of promos. Ash – all those guys would send me promos. Because I sorted them out with clothing. It was a good trade initially, and it got me to have records nobody else had, and then I’d put out a mixtape, and the mixtape would go crazy. It wasn’t like a plan of any kind; it was just all happy accidents, you know. And, just trying to meet these guys I would read about in Prestige magazine. Atmosphere – Jay Frenzic. He came over here and played a show, too. Anybody who wanted to come over could stay at my house, or if they wanted to get a hotel, that’s fine whatever. You know it was fun, man. I think back to those days.

Did you ever go to the UK?

JEFFEE: No, I never did; I always wanted to. AK did a few times, and my little brother [Kingsize] went over a couple times. I always had a whole bunch of cats at my house. I also had a day job, and I spent all my vacation time skipping out on a Friday or something like that to go to a gig, so I never had much vacation time. Now, I kind of regret it because my little brother lives over there, and I still don’t go over there. I have two dogs and ten cats. And I have to coordinate with my girlfriend, stuff like that, Sooner or later that will change.

I feel like I know it, just from knowing everybody and talking to Marvellous Cain’s mom on the phone. I’d answer the phone, and he’d say, “Muuuuuuum” because he lived at home forever. I remember he was like, “Hold on, hold on, Jeffee… ‘yeah, Mum, I’ll have two sausages’”. It was just funny. Super nice people. Everybody was super cool. I mean, SS used to come over here all the time. We used to trade clothes right off our backs. He’d be like, “Hey, that’s a cool DKNY shirt”, and I’d say “that’s a cool jacket” and we’d trade. I felt like I knew what was going on. I think, early on, we got a VHS cassette tape in ’92 of some rave over there, and we must have watched that like 900 times. It was Mickey Finn DJing. I mean, I knew about all those guys doing early raves out in the field and stuff and getting arrested. Before that, I was really into UK pop bands in the 80s, so I’d buy all the NMEs and Melody Maker magazines like that.

Was it always ragga Jungle for you?

JEFFEE: I always stuck to the ragga side of things. I was a massive fan of The Scientist, and those early records of him, and then dub records and all this stuff just came together at the right time, and I was like,” Man, I know that sample.” I knew where it came from because I had all the same records. The funny thing is, all the reggae guys over here in Orlando really loved Jungle because they were all British Jamaican – they would come over and live in Florida… and it was because of this I managed to see rudeboi Rodigan over here…

Likewise, when I was in Pittsburgh, I grew up with Dieselboy. He would play all those early raves, too, but he played all the dark stuff, and I played all the ragga stuff. So, he got ragga ones that he didn’t like, and he would give them to me, and I would get some scary Reinforced record and give it to him, and we’d trade back or forth all the time.

In a similar vein, the way in which I found out about you was through your Jungle Spliff tape, which is a bit an of extravaganza in ragga Jungle.

JEFFEE: Right, that had a lot of tracks in it, man. I was getting worn out by the end, you could tell there was a little bit of dragging at the end right. [On YouTube] I see it and go ‘damn man’, I remember I had to have 30 seconds of every song and if you saw me play at a rave back then, you almost saw me do the same thing. I tried to keep myself entertained by going from drop to drop to drop. It was kind of my thing. So, when I was done DJing, I would have a stack of records like this [gestures splayed records]. And I didn’t have time to put them back in their sleeves, so I had to put them all back at the end of the night. They all played, and sometimes I would find a scratch on them. Sometimes, I’d see DJ smoking a cig, drinking a beer, and talking to somebody. I was more like I wanted to put on a show.

I’m glad people like that [The Jungle Spliff YouTube tape]. Ruffneck in Toronto was my inspiration because he would play an M-beat record, bring it in, and then bring another record in and then back to the M-beat record. I just liked it. I knew all those samples from the M-beat records because I was into dancehall and ragga. And I was all about the samples. I think that was what really intrigued me about all that stuff. And the secrets behind it. Shut Up ‘n’ Dance was really good at that. But we used to try to squeeze out as much sampling time as we could for all those E-mu samples we used to have. If you look up the ‘Heavy Stompin’’ EP, it has two guys from Mortal Kombat fighting each other. I did the label. But that was the same with the samples.

Did you feel that futurism when you first heard it?

JEFFEE: Yeah, I felt like it was something new, and the sounds they were using were different. You could get away with anything, and I felt that was a challenge.

Speaking of futurism, and YouTube, what was your first experience with the early web or internet in general?

JEFFEE: Well, I lucked out. I went to Penn State University and dropped out. But my younger brother [Kingsize], who lives in Brighton, was going to Youngstown State in Ohio, and he had the early version of the Internet where it was all just text, where all you could use was chatrooms really [USENET] – the early version. I mean, before the Internet, it was obviously different. It would be handwritten flyers with Dieselboy on them, and he misspelled my name as Jeff-ee. It was just all happy accidents, man. Somebody would run into somebody else, and we’d figure it out because there was no internet to find out about anything.

I mean I used to cold-call record stores and ask what their jungle selection was. I would do that and order from England all the time because I worked at a hardware store, and they didn’t keep track of the phone bill, so I could call England when nobody was looking and order the records right. I was doing that all the time – I was on the phone listening to records when they sat the phone down by the needle so you could hear it. It’s so funny, man, because I think about when they got that bill – “Who the hell is calling England all the time?!?!?!?” because that was back when an international call was ridiculous, right man. I remember my phone bill was 600/700 dollars a month because I’d call Marvellous Cain and cut back and forth.

But getting on to the Internet properly… I was in the graphic design world, so many people would come in and say, “Hey, man, can you design me a website?”. Nobody knew a lot about it, but there was Adobe Pagemill, and I figured it out. So, I started doing websites for people. I want to say maybe ’95. But because I was still in the print world, Junglized got printed. I’d pay the money and get it printed, stuff like that. When the Internet finally came around properly, it was crazy, I remember saying there’s no real sense of me doing this [Junglized] anymore because the Internet – you could just put it all up there. It’s there forever, you know.

In my graphic design day job, about ’97 to about 2000 or so, my boss was drunk all the time; he would drink at lunch and go pass out on the couch, so I was on the Internet doing my website, booking shows, like all afternoon man. I had my own office, so nobody really knew what I was doing. I got all my work done in the morning, and then I just booked shows all afternoon. Since I was the guy who did the websites at that job, I had access to the Internet, and nobody else did. I had the dial, and you could hear me getting on the Internet, you know, like the really loud thing, and the boss didn’t stand up or do anything because he’d say, “he’s the internet guy, he needs to be on the Internet”.

I never got around to typing up the old stuff and putting it up there, and so I just made a history of Jungle based on my experience and put it on the website, starting with Shut Up ‘n’ Dance and how it evolved from there. At that same time, this magazine called Synergy from Tampa (this was the late ‘90s [1996]), said, “Hey man, since you do Junglized would you wanna just incorporate it into our magazine” and I said yeah. And it worked out well for me – I no longer had to pay for printing. Then there was that history of Jungle thing that I transcribed from the Internet, and then there was a picture of Rudeboy Monty. So, I started doing it there, which was much more manageable. I still had to do a lot of the work and interview everybody, but they got it printed, looked nice, and came out in a shiny magazine.

When people ask me what Junglized was, I say it was like a little fanzine that connected people before the Internet, and then once the Internet came, we all knew everybody. We could call each other, get on there, and chat with everybody. Back then, [the Internet] was like a new coming into the… to me, it felt like more of an information age thing, but you know, it’s been taken over by advertisements. It’s the only way to advertise; nobody prints anymore. In music, you don’t print a record hardly anymore. I feel like I was really interested in having a website so people could book me, and that was the thing I remember when I first…. “I gotta get a website, I gotta get a website”. You know I put up some pictures, but I never thought of advertising of any kind. Even when advertising in Junglized, I gave everybody their ads for free. I think that was probably my downfall in general, I should have had a manager. I booked everything myself. If the show was a flop, ‘just give me 50 bucks’. That was my problem. But I wasn’t doing it for the money at all….

[This interview was originally recorded and published in April 2023]

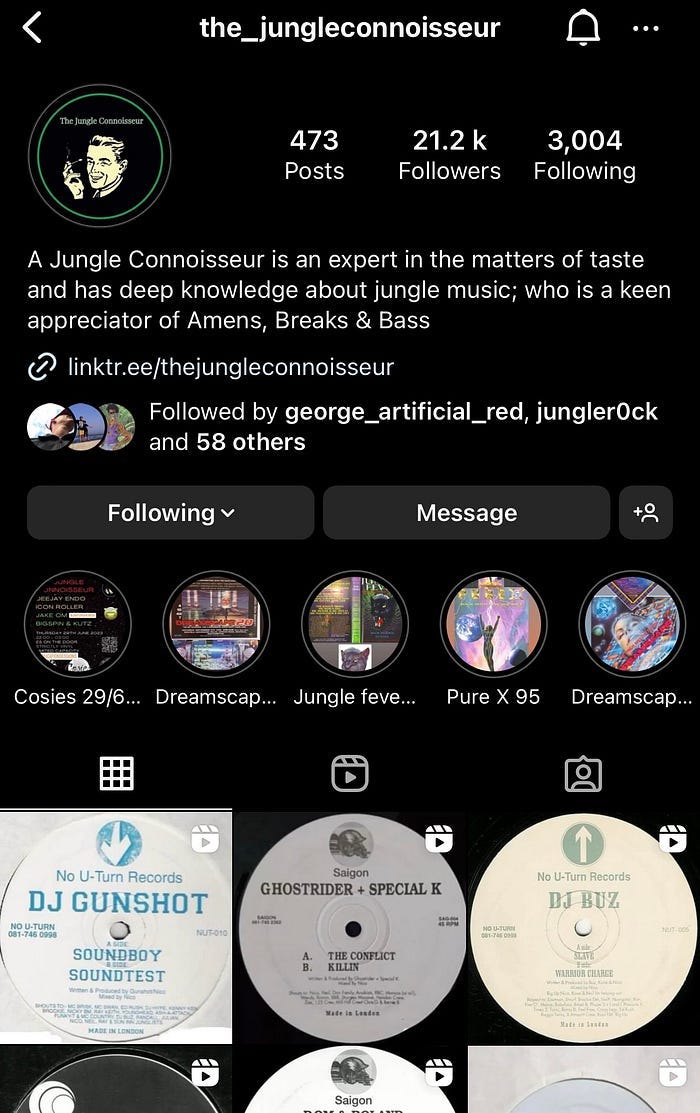

So within the fourth chapter of this series I wanted to have a chat with a fascinating figure and a man who is putting it on within the modern day Jungle scene: Jon Stockwell aka – The Jungle Connoisseur [https://www.instagram.com/the_jungleconnoisseur/].

I first came across The Jungle Connoisseur’s Instagram page when he posted a reel of Dillinja’s ‘Ja Ya Know Big’, the B-side to Dillinja’s classic ‘The Angel’s Fell’, around May of last year. And since, the page has just gotten bigger and bigger, with 21.2k followers as of April 2023. And thus, in March 2023 The Jungle connoisseur hosted, along with a number of other wax djs such as Dj Azure Dee Jay Endo & Artificial Red, the page’s first live event. A classic of ruffneck ragga, soulful tunes and amen tearouts in the basement of the Crown in Bristol, it had all the makings of a first rate night. Nutty bass and sound system courtesy of Dharma Hi Fi, low ceilings, and enough sweat to fill an ocean, the DJs dug deep to bring out their best tunes. And so, it seemed fitting to document this and delve a little deeper into how the page and events all came about.

Before delving into mine and Jon’s chat, I wanted to explain a little about the page and also the context of the article. The popularity of The Jungle connoisseur’s page is part of what can only be described as a perceived ‘resurgence’ in demand for authentic Jungle, but most importantly it’s a demand for the archival of the genre’s material. Pages like MickeyBeam75 and BackinthedayJungle are further signs of such an occurrence. As many ravers settle down and reflect on what was, pages such as The Jungle Connoisseur and the aforementioned Youtube channels provide refuge for lost memories and dubs that ravers and DJ’s had all too well forgotten about. And importantly too, like my previously mentioned example of Ja Ya Know Big, The Jungle Connoisseur is putting it down for the B-sides, the ones ravers might have heard on a pirate many years ago but it might never have really gotten the light of day it deserved during the golden years. And so, new life is given to these tunes; where these tracks develop a cultural currency stronger than a classic and revered tune which was mixed in sets multiple times a night. An example of this would be Baraka’s ‘I’ll be There’. What we see then is of course the increase in price of these tunes but fascinatingly the creation of a paradoxical new (sort of) Jungle scene with old tunes that might only seem new due to their relative lesser-known status. An example of this would be the track ‘Jungle Rock’ released as a white label on Street Tuff records in 94′ . Simultaneously, where The Jungle Connoisseur manages to differentiate himself from others archiving material, is the physical aspect associated with it and the page. The true essence of these tunes and the music is only really grasped when it’s physically experienced. It’s all well and good experiencing everything through the internet, but much of what makes the music so special (ear-shattering bass) can only be felt in real life. Here’s what The Jungle Connoisseur has to say about it all.

Me: So Jon, how did you get into Jungle in the first place?

Jon: I first heard about raves when I was about 10 years old, around 88’. My sister came home one time talking about “Acid House!” and I remember thinking Acid house? That sounds like a strange type of music but I was intrigued from then on. My family was always musical though, especially my mum, she used to play stuff like Motown, Soul, Funk and Disco and so I always liked that sort of stuff growing up.

I remember around the same time there were formative albums Rap Trax ‘Megabass’ and the Deep Heat compilation albums that had a style called hip house, a mash up of hip hop and house. Really liked that as a young kid. I used to record house music onto cassettes from the radio. Graham gold, Pete tong etc. It was around 90–91 when I moved from a village to a town that I became more aware of rave music and raves themselves. A lot of the teenagers were ravers around my area and it was a big thing in school, especially the later years. I was fascinated by it. The whole culture and its underground nature. From merchandise to fashion and of course tapes – rave tapes from all the big events at the time. Used to walk around with my pockets full of tapes for the Walkman – mostly live recordings of events or big raves and I’d think wow! Events like Universe & Fantazia and Obsession. If the dats were good…You could hear the crowd and the buzz of the event!!

I grew up in a small market town called Newbury in Berkshire. Its just off the M4 corridor between London and Bristol. South Central as I used to call it, Newbury sits between London and Bristol, almost right in the middle. Fantazia did a big New Year’s Eve event at Littlecote house near Newbury. Think I was around 14 at the time, 20,000 ravers on your doorstep, I think it even made national news as most of the big events did back then. And just like that I was hooked! I wanted to go to all these big raves. To Experience the music and the atmosphere that was off the scale on the tapes we were playing and videos we were watching. There was also a local record shop in Newbury called Whirleycog records which would have a table outside with the latest flyers that the promoters would drop off. I would go down there and snag two of each flyer – put one on my bedroom wall and keep the other in a box. They also sold tickets, merchandise and tape packs too…

I was about 15/16, the time came and I went to my first Dreamscape. And by 1995 I was attending raves like Universe tribal gathering, Dreamscape, Helter Skelter etc. I was going to a lot of big raves and particularly the Sanctuary in Milton Keynes. I got the raving bug! From house and trance to gabber techno and even happy hardcore – I liked a bit of every style. I had a thing for techno for a few years dj’s like Colin dale, Trevor Rockcliffe and the harder more gabber side of Techno dj’s like Clarkee and the Producer attending the infamous Technodrome at Helter Skelter. At the Sanctuary, the upstairs Room/Room Two, the floor used to flex a lot due to all the stomping that went on. The decks were suspended on chains. Crazy scenes…

Me: You say you remember the changes in music from ’88 to Jungle. Were you hesitant at all towards the shift to breaks and bass around 1992/93?

Jon: No not really I would have only been around 14 so it was like a new sound anyway, I loved the breakbeat element and was hearing a lot of breaks in hip hop and bass early 90’s. So that’s where I heard a lot of breaks first, but, mashing up amens, adding other elements and samples changed the game and with 93’ being a pivotal year for rave music and defining of styles.

I was into a lot of the music, but I enjoyed the more Happy Vibey stuff that was upbeat but still had breaks. People like Slipmatt, Seduction, Dougal, Vibes… I loved breakbeat hardcore because everyone was happy and Jungle was a bit more moody so because of that I was a bit hesitant at first. But by 1995 though for me anyway it was all about Jungle, all about One Nations, Jungle fever and desert storm, telepathy etc. You would see the odd incident here and there at raves and sometimes you had to watch out for pick pockets etc. rude boys and girls. Same as anywhere really, some bad eggs trying to ruin peoples vibes. The Sanctuary’s security for instance was basically run by gangsters, you would always have some trouble with them praying on people getting messy and stealing their drugs and sometimes giving them a beating. I got a few stories of some things I witnessed first hand there but we’ll save them for another time. CS Gas Etc. Sometimes You would get people firing blanks at the ceilings. I saw that happen at a Telepathy event, a guy blasting a gun into the ceiling right next to me at the event at Club EQ Or The Wax Club as it used to be known in Stratford East London; not going to lie that was a bit scary. Always preferred the bigger events at the time, Dreamscape, One nation, Helter Skelter – Keep the Fire Burning & Best of both worlds. Devotion New Year’s Eve in Cardiff CIA ‘96. And then I continued into ‘97 but by then jungle had morphed and changed into Drum and Bass – the golden era of drum ‘n’ bass 97–99’.

I think with Jungle people don’t realise it had a really short lifespan, it was a time and era. ‘93 to ’96. That’s the era that I love the original foundation but by 1996 it was changing and going away from the ragga vocals and amens, more towards tunes like Badass by Micky Finn and tunes like shadow boxing by doc Scott and a step towards to the more techy stuff, DJ Trace, Nico, Ed rush & Optical. Jungle and amens have always had an influence but by ’96/’97 it was all about Drum and Bass.

Me: Do you like the Darker techy stuff that came in the late-90s, stuff like Ed Rush, Bad Company etc.?

Jon: Yeah I do, As much as I love Jungle, I love Drum and Bass. Bad Company’s ‘The Nine’ was the late 90’s banger that still goes off today. A lot of the Jungle Producers at the time started making Drum and Bass. Ed Rush was originally making Jungle on No U Turn with Nico. The scene as a whole just progressed at a really fast pace – as did Drum and Bass. I love Wormhole by optical and Ed rush. It’s one of my favourite D&B albums… I had some of the best nights of my life in Drum and Bass raves but I’ve always had a love for Jungle.

Me: Who was your favourite DJ that you listened to on tape packs and things?

Jon: Probably Tango man, RIP. His tunes and his production were on another level for the time. ‘Tales from the Darkside’, ‘Further Intrigue’ – those darker Jungle tunes. He was ahead of his time. He was making stuff in ’93 which could have been released a lot later. I loved Easygroove, Ratty, but then also my techno DJs like Colin Dale, Colin Favor & Carl Cox. Mickey Finn, Kenny Ken, Nicky Blackmarket, Hype and Brockie. Had a lot of love for some MC’s too Early 90s MC’s Such as Ribbs, Robbie Dee, Joe Peng, and Mad P to Fearless & GQ and Stevie Hyper D & Skibadee, RIP. The 90’s was just a mash of styles. Raves like Obsession playing Hardcore, Techno, Jungle Techno all on one night. It would be so many different DJs playing so many different sounds. It wasn’t like a one style rave or music like it is now. It was really cool at the time. You would have ravers come to see the Techno DJs and they would all leave when the set was over and then the Junglists would come and see the Jungle DJs. The crowds would swap over and the vibe would shift from one style to another which was mad to see.

Me: You mention that you were going to Dreamscape when you were 15/16, which is pretty young, was everyone else a similar age a lot of the time?

Jon: There were a lot of underage people going to raves back then. Today that’s a lot harder. Back then, it was relatively easy to get into a rave. There was a lot of 14/15 year olds getting into 18+ raves and looking back on it now, that’s crazy! Not sure it would happen nowadays. A lot of young people started raving early, on account of their big sibling usually. And it just shows how raves and raving swept the country. Loved the fact that Jungle was a British thing and from the streets. When you got into a rave, it was a vibe thing, it was a happy thing. Every stranger was your mate and people came from all over the country. People from Scotland, people from Liverpool, people from down south going up north and vice-versa, people would travel as there were raves happening all over the country. Your local scenes and then you had your national scene and that was a cool element.

It wasn’t all necessarily about the big raves, it was also about clubs as well. One of my local clubs was Brunel Rooms in Swindon. It had an awesome revolving bar. The fruit club was held there in the mid to Late 90’s and then around 2005/6 with the Valve sound system nights there; Dilinja’s nuts sound-system. Brunel rooms has Legendary Status! It was once the longest running independent nightclub in the country. Goldiggers in Chippenham as well, One Nation did a few events back then. A lot of people would travel to Goldiggers regularly. I have about 4 ring binders of flyers of events at diggers, Brunel rooms etc. I had hundreds but kept the best ones in ring binders. I Used to collect merchandise from the raves I went to, tee shirts, bomber jackets etc but used to give away a lot of what I collected strangely enough.

Me: In terms of the history and collecting, were you buying records when Jungle was beginning?

Jon: The first ever 12 inch record I bought was in 1991, it was 2 Unlimited ‘Get Ready’. Hilarious! But I was like 12/13. My second vinyl was everybody in the place by the Prodigy and my 3rd was ‘Playing with knives’ by Bizarre Inc and then something by Altern 8! By 16/17 I would go into London occasionally and go to places like Mash in Oxford street and that was when I first got to know about records. Blackmarket too. One summer my mate lent me his decks for two weeks, around ’97 I reckon, and I learnt to mix with the two records he gave me. It was Scorpio ‘Trouble’ and Krust ‘Warhead’. And by the time he got back I learned to beat match and mix two records. That was a great feeling! Started to buy records regularly by ‘97.

Me: Those tracks mix very well!

Jon: Exactly. They do don’t they?!?….I didn’t really want to be a DJ when I first got into it for some reason. It was Gemini direct-drive decks that I learnt on with a Gemini mixer. I got my first proper decks in around 1999/2000 – Vestax decks which I still run today. Some mates and I set up our own little crew called Dub Rollers and we did some party’s in our local area. And that is how my career as a DJ really started. We are all still DJs as a matter of fact, all four people who set up the crew originally.

Me: Were you mostly playing current tunes or were you playing some older stuff?

Jon: Well as the music progressed so did you – as a DJ you always want to play current stuff or stuff people haven’t heard but it’s also good to play older stuff that perhaps people haven’t heard. I got to know a lot of the older tunes from older friends of mine that Dj’d back then. Another friend of mine was selling some old early-90s tunes like ‘Obsession’ by DJ Vibes and ‘Trip to the Moon’ by Acen. The slammer by Krome & Time. I would then learn the history of it all these tunes and I’d remember some of these tunes from tape packs. Sometimes I would pick up tunes in second hand record shops and not really know what they were. Then I would get back, put them on the deck and play it and go “oh yeah it’s this tune”. It was pure luck really.

Me: No Discogs back then

Jon: No there wasn’t… It was all about the shops and the second hand record shops. Another thing that ties in, is that my local record shop was the Record Basement in Reading. And obviously associated with them was Vinyl Distribution who were responsible for the great majority of Jungle record distribution in the 1990s. And Basement Phil of course ran some labels. He did the Photek stuff, Source Direct street beats etc etc so many labels and tunes came out of vinyl distribution and the record basement. I had a part time job at Sainsbury’s around ‘96/97 and I would get about 100 quid in wages and go up to basement and blow most of my wages on records.

Interestingly enough, vinyl distribution went defunct [around the turn of the millennium] but Basement Phil set up a new Distribution company called New Urban Music with Mickey Finn in my home town Newbury. Tobie from Serial Killaz worked for them and that’s how I met him and Phil. We used to do a regular Sunday night DnB thing called 36th Chamber at a pub in Newbury called The Tap. A small long backroom that used to get absolutely rammed! The night ran for about 10 years. I used to MC at these nights. Some big names would come down there – Ray Keith, Nicky blackmarket, then Sub-focus before he was a superstar, and ‘king of the jungle’ DJ Dextrous. That was about 2001/2002. Absolutely wicked vibes for a Sunday night!

Remember also going down to Blackmarket records on a Saturday sometimes and it would be rammed. Most of Soho was great too; Sister Ray records. Chemical Records in Bristol was an interesting one too. They were an online record store and they would drop promos every Thursday by this point we had the internet 97–98. Capapult in Cardiff was also a good record shop and massive in Oxford.

And it was because of the culture and a way of life that I started that shift from being a raver to wanting to DJ and know every tune being played. For instance, every Thursday afternoon, about midday, you would get onto Chemical and see what promos they had. But they would only have four or five of each promo. You’d get the promo but then your mate wouldn’t. And between us DJs that would be a bit of a competition, a friendly rivalry of who could get the best tunes or promos in any given week.

I had accumulated a ridiculous amount of records by this point, like thousands of records. At the time I had about 5000/6000 records and now I have about 1500. Moving about 30 odd boxes of records when I would move house was no good or fun and so I had to slim down my record collection. I will always be a record collector and keep buying records and every day is a school day though. I think I know a fair amount about Jungle / DnB but there is so much out there I still don’t know about. So through the Jungle Connoisseur I’m still learning about labels and tunes and the ones that I missed.

Me: In terms of the page, what’s the process for choosing a record then? Do you own a lot/many of the tunes you are posting?

Jon: Yeah I do, I own quite a lot of what I post. But then there’s tunes that I don’t own that I would like to own. There are tunes that are £100 – 150 that I can’t really justify buying. For me, it has to be worth it. And even then, I will see the price of a tune and just think back then that tune would have been a fiver. Like your conversation with me at The Crown, asking if Tom & Jerry are worth it. Certain tunes are worth it. It amazes me how expensive a tune can be and what makes it expensive. Is it because there was only a few pressed? The rarity? The popularity of it? I still don’t know what goes into making a tune expensive on Discogs. I guess when a more unknown tune is put on discogs and there is only 2 of them and 1 is snapped up for a fiver and the other a tenner. It’s then a 10 pound tune very quickly. The price can then be raised again etc.

Me: Do you reckon you have a part to play in a price increase in tunes? Like you posting a rare tune and someone new finding out about it?

Jon: Maybe I do without realising: see if I post a rare tune, people will then go and Discogs t straight away. Because I get a lot of people commenting that they just discogs’d it and found out it was hundreds of quid. I guess you have to be serious to spend that much on a tune. I’m putting what I know about Jungle out there for people to use as a resource that I didn’t have back in the day. There’s no set routine. What I post it can be quite random to be honest.

And again, with back-catalog tunes there are still so many to be discovered. There are some labels that only released 4 or 5 tunes and then went defunct and are pretty obscure. And then there are those larger labels such as Moving Shadow that did over 200 releases. It’s hard to know everything about all the tunes. I read somewhere that between ‘93 and ‘96 there was 15,000 tunes that were released. I’ve posted about 300 – 400 tunes and potentially there are another 13/14 thousand more out there that I still haven’t posted. And I’ll keep posting until I’ve exhausted all resource but that’s gonna be years and years from now. There are however lots of tunes I can’t post due to certain copyright issues.

Me: How did it come to be?

Jon: It all sort of just happened when I was going to bed one night. I was just thinking how can I create a platform for Jungle music for people who don’t know about it or people that do remember the time and want a place to share memories. It’s for the people that know and for the people that don’t but want to know. I’m aware I’ve got quite a few young people following me that want to know about Jungle music and think it’s great that the younger generation that want to find out about jungle music. All styles too from jump up jungle to intelligent jungle such as Photek, There’s a massive spectrum to it.

I’m grateful to be able to do The Jungle Connoisseur and bring my vision to life though the page and the events and also grateful to have experienced the early days of jungle and and rave scene. I’m also grateful to be able to tell some of my story and continue to DJ and now dipping my toe into events and hopefully leaving my mark and contribute to the jungle scene going forward. Jungle is a UK thing that’s gone world-wide. It started off with humble beginnings. House music started it off in America with Detroit and Chicago, it came over here and we added a mish-mash of sounds from funk soul and samples to amens, breaks and sound-system culture… and jungle was born. And that leads us to modern-day Jungle. People always say it’s in resurgence and that jungle was dead or that it got cool again but Jungle has always been there and it’s always been fashionable and I’m grateful of course to share what me and others, experienced back in the day and long may Jungle music continue to thrive.

And finally I want to say respect and thank you to Jon and everyone who has and continue to make Jungle possible.

There have been a number of jungle tunes on my mind lately that I cannot seem to get out of my head. And as the title suggests, these are ’94 tunes typically sampling rare groove/ RnB records. But what is so indescribable about these tracks is that without doing too much to the original sample (it seems just by virtue of programming these samples through clanky 90s hardware) they manage to make the track something so entirely different, euphoric and ‘ardkore.

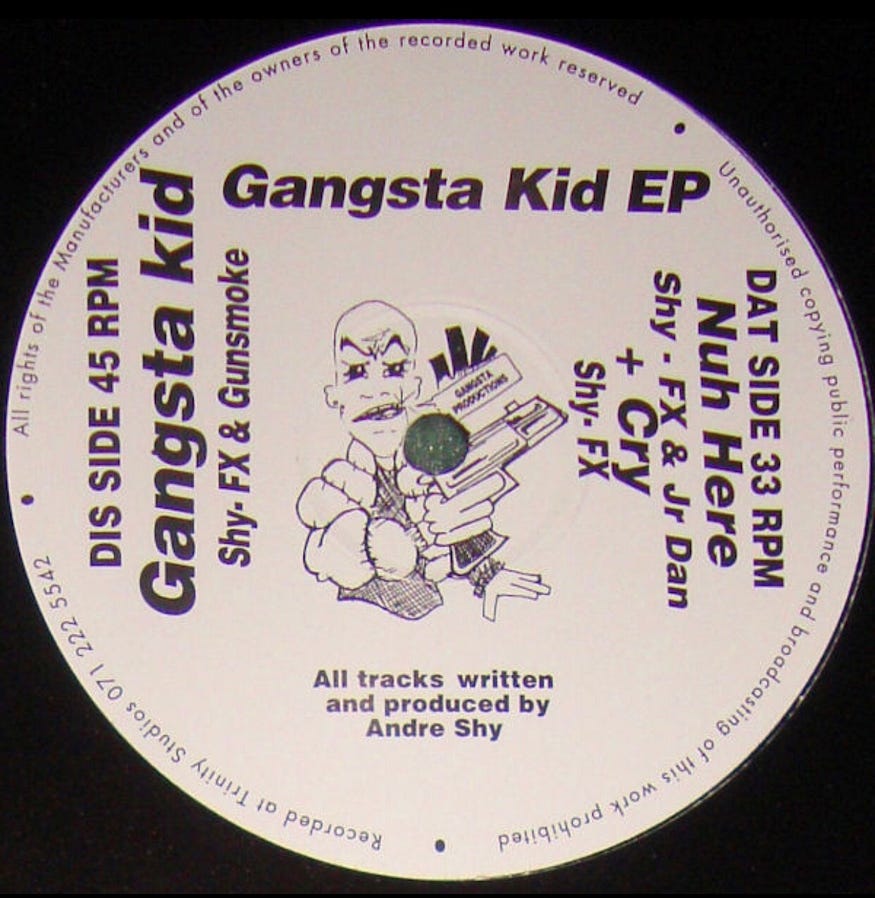

The first tune is Shy Fx’s ‘Cry’ off his Gangsta Kid EP (his first release I believe) and it samples Jodeci’s ‘I’ll cry’ from 1993. A rather unremarkable original source, Shy Fx opens the track with the sample, speeding the lover’s voices up to the max and then intersperses it with a hardcore ragga sample. Simple but effective. Noticeable is the sort of lo-fi quality of sampling in Shy’s tuuune. It sounds as if it’s been sampled about 3 times over already and he’s ripped it from that. But this adds an indescribable feeling to the tune and elevates it beyond another ‘94 jungle tune which might break out into a rare groove sample halfway through.

Next up is a tune from the absolutely don that is Potential Bad Boy. Personally my favourite producer, he too has a knack for making a great volume of disparate elements come together successfully and elevate the samples being used. Have no fear samples R.K*lly’s ‘Sex Me’. Pitched up and sped up, the sample is backed by an utterly ridiculous combo of breaks, bass and pads. When it breaks out into “I feel soooo free tonight” it takes the tune onto a higher plane. In a strange way, the fact that R.K*lly is such a horrible individual gives the tune a strange edge which makes it all the more ‘ardkore. The euphoria of the first half swiftly breaks into dark and cavernous stabs, blending perfectly that wonderful ‘93 into ‘94 sound. And again, like the Shy tune, there is a quality to this tune indescribable. It sounds as if it’s been ripped from a ‘90s RnB album and flown through 3 generations of sound, creating this lovely blend of nostalgia and futurism. ‘Ardkore Jungle Tekno at its bloody finest.

This is the start of another blog series I will be publishing discussing architecture and the built environment. It will discuss all things Modernism, how we navigating our surroundings, housing, and more. In the meantime listen to Fishman’s Weather Report and imagine yourself floating above the clouds of Tokyo… Stay Tuneddddd

¶¶¶¶¶

¶¶¶¶¶

¶¶¶¶¶

¶¶¶¶¶

¶¶¶¶¶

So to kick off what is the second part in this series exploring Jungle I contacted Owen Hatherley. A fount of architectural wisdom and expert on Modernism; this was to understand his perspective on the relation between music, drum ’n’ bass and cityscapes. Having seen that he was a fan of Eddie Otchere’s Junglist, it seemed fitting too.

Owen needs little introduction regarding his background, but I will mention the immense impact his book ‘The New Ruins of Great Britain’ had on me. As a general explanation, Owen remains sympathetic to Modernist architecture, particularly post-war design, as it was a time in which architecture remained truly experimental and oriented towards bettering the lives of the working class. And yet, the period has received plenty of disdain and demolition from various detractors, unaware or disgusted of what it represented and envisaged. Thank you to Owen for his insight on British architecture.

Me: The first question I wanted to ask is a much more general one. What do you feel today is the relationship between the musical stagnancy that exists, in pop music and something such as the Hardcore Continuum, and the architectural stagnancy we see today, as explored in much of your writing?

Owen: I think one can see infinities between music, electronic music, pop etc and architecture. But they really stay at that level, as you are dealing with one of the fastest art-forms and then one of the slowest. You know a building takes at best, at the very fastest, a year or two to build. Frequently it can take a decade to construct. In popular music, a decade is a very long time indeed, even now. What was happening 10 years ago is very different to what is happening now. The temporalities are just so different. I don’t think you can compare their level of speed or innovation or anything like that because it often doesn’t really work. And also the way that their internal processes of innovation can change are just really very different. There has never been a moment in architecture, even at its very fastest, where you would see a change that you would get in the mid-sixties or the early-90s, where within six months a scene would be completely transformed. Thats impossible in architecture. So i don’t think you can really run them together in that way. I do think there is a question about environments however. To get a sense of that process of non-synchronicity, I don’t think there is any 1960s pop records that mention new-towns or tower blocks. At the time in which they are being built, no one is talking about them, its just not there. By the late-70s, by which that stuff was already incredibly unfashionable architecturally, and it had been standing for a while, it then features constantly in Punk and Post-Punk. So you have got these totally different streams that are happening, in which for sure, the speed of innovation slowed down in both. But at differernt times, in different ways and in different speeds.

Me: That makes sense. I’m aware you spoke about Hulme Crescent in New Ruins of Great Britain and how that fostered the punk and post-punk scene in Manchester. Do you feel as if the music produced in the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s and ’90s had a direct or even quiet relation with the modernist architecture produced in post-war Britain and how do you think this best manifested?

Owen: Yes absolutely. There is all sorts of times in which there is a relation, with the aforementioned provisoe that its usually not happening at the same-time. Hulme is a rather interesting example of that. The thing that makes it a centre of pop-music is its failure as a kind of ordinary housing. By the time its less than 10 years old, Manchester city council basically stop housing families there. It becomes incredibly hard to let, it becomes centrally squatted and the council were basicallly giving them away, oftentimes to people who were in the music scene. I don’t think that involves everyone that lives in Hulme crescent. Im sure there are lots of people that had very little to do with it. But you had this real disproportionate concentration. But the reason that was able to happen was because it wasn’t a successful example of social housing. There are other times in which there might be more successful or mundane social housing that guest feature in music. For instance, the guy from Hefner that did an album on Harlow New Town. It [Modernism] kind of turns up later and in Ghost-box as an object of nostalgia. I think often from people kind of raised in it, or have it at a great historical distance. Then the other thing I think is people starting to register or talk about living in tower blocks. The Clash is obviously the very big example. Despite the fact that Joe Strummer was extremely posh, Mick Jones was not and lived in one of the big high-rises near the West-way that looked over Harrow road. So that turns up loads in early clash Records. And you can kind of go through a lot of post-punk records and find various references to different Modernist housing, Modernist Housing that had almost all been built by the end of the 1960s, that is very seldom being built in the seventies.

By the end of the 1970s post-modernism had already won the argument that modernism was over. Because of the fact that it becomes housing that is very very cheap, you have it being kind of connected with young people, as often they don’t have much money, at a point when council housing was very hard to let. It was being given away a lot, particularly to students and such things. Pulps various records touch on council housing. They lived in council housing in London, after being students, rather than in most cases in Sheffield. So in sheffield it was a thing that another group of people lived in. And of course when you are dealing with the hardcore continuum, you are dealing with a multicultural working class, that in a lot of cases are living in modernist housing. Although, its [the Hardcore Continuum] a lot more suburban than people give it credit for. Theres a reason the record label is called Suburban Base. Its very big around the M25, around many of the new-towns and so forth. Its not like everyone there is living in high-rises in Hackney. Although a lot of people are. And high-rises of course are a very good place to put pirate radio masts. Thats why there has been so many pirate radio stations placed in tower blocks. So thats just a backdrop a lot of the time, in Grime videos it was always a backdrop. Sometimes its a backdrop where somebody might actually live like Crossways estate in Bow because a lot of people involved in early Grime like Roll Deep and Ruff Sqwad had always lived in the estate. But then later it sort of just becomes a concrete backdrop. Skepta’s video is set in the Barbican. And of course if anyone knows their architectural history, the Barbican is… you know, even skepta would struggle to afford a flat in those towers now. It does the grime video thing of, we are in the mean concrete streets, here we are.

Me: Yes! I suppose with the architecture being produced today, do you feel as if these new awful clad panelled high-rises you see on the approach to paddington on the train, will be the places of music production in 20 or 30 years time?

Owen: Yeah, I mean I have to sort of plead the fifth on this, I don’t particularly know too much about new music. When music has turned up in recent years environments, it seems to be either in Grime and then Drill, where it turns up as a kind of like, we live in the slums and they are made of concrete. Or its a kind of a fantasy futurist city that features a lot in vaporwave. You know the kind of environments that are a sort of permanent japan circa-1982. Thats where that is. The new environments, it is tough to say. But, how one would connect them to those two things is quite interesting. A lot of those very very bleak student high-rise flats there are so much of arguably serve a similar purpose to what Modernist council tower-blocks were to post-punk in the late ’70s. A very alienating environment. Because they are… extraordinarily alienating. Beside how cheaply mass produced their construction quality is, they’re also very small flats, very enclosed, discourage leaving the complex a lot of the time. In the pandemic they were frequently closed off. So you know maybe those brightly coloured student flats will turn up in pop-culture in some way, it would be interesting to see that happen. And I think a main experience for a lot of people in London, is poor quality rental housing, which is usually not in new buildings. It is usually in Victorian stock that has been subdivided. That is the basic environment for downwardly mobile youth in London. They don’t live in those new high-rises by-in-large. And even in the student ones, its generally more affluent students and Chinese students that live in them. But they are all around, so I can evisage them certainly being in that new music environment.

Politically, I’m obviously very sympathetic to that period of architecture [Modernism], but the people who have made it a part of their music generally are not. Which is one reason why I sort of fasten onto something like Pulp or the Human League because they actually seemed to like Modernism. They liked living in Modern architecture. Which is interesting because it is the exception to the rule. Most of the time it is treated as a very alienating environment. But this also drags onto another question, which is one that Journalism on music nowadays focuses on a lot, can people afford to make culture or music given how expensive living and housing is? And again, it seems to happen but yeah it is a major question that I don’t really have the answer to.

Me: So speaking more in terms of Jungle then, I noticed you did mention the novel Junglist in a previous interview, how do you feel [both novel and genre] that they related to the architecture and even the mapping of cities?

Owen: Yeah I mean there is a whole passage early on in Junglist talking about how rubbish it is living in a tower block and how terrible they are. And that is a classic example harking back to the Clash ‘slums’ and where we are forced to live idea. Whereas now, that housing is so inaccessible, you either have to be phenomenally poor or phenomenally rich to live in it. Or you have to have grown up in it or had parents who grew up in it. But otherwise getting council housing now is extraordinarily difficult. I imagine because of the way the waiting system works, you have to be in pretty extreme penuary to get it now. Which again is why it probably turns up quite a lot in Drill, because I imagine quite a lot of the people who are involved in that are in extreme penuary. But, whereas, when talking about something like Suburban Base, Jungle and Hardcore were full of a lot of people who weren’t quite as hard as they made out. Like Pop Music is in general, a lot of the kind of post-60s music… You know I am a firm believer in Simon Reynolds Liminal Class theory that it comes from people that are one class rubbing up against another. And there are people who grew up very very poor, Tricky or Goldie being very good examples, who then make really interesting music. But then they are also in that sort of rubbing up one thing against another category. Both of them being mixed-race is once example of that. The fact that both of them were really into post-punk and goth and synth-pop. So you know they had these multiple worlds existing and thats how they were able to do what they did. But of course ‘Inner City Life’ can be pretty miserable and living in tower blocks in Hackney can be miserable . That is what you generally get from this music [Jungle]. But because of the kind of futurism that is running through it, that makes it a little different to the Clash version of things. Its quite similar to post-punk in the sense that it has its cake and eats it. ‘We think this is terrible and alienating but its also really exciting’ . And late hardcore and Jungle is absolutely full of that. That dialectic of, its horrible but also really exciting. I mean we are dealing with kids in a lot of this and I think thats a very young person’s reaction to their environment a lot of the time. This is really cool and exciting but horrible.

Me: Yes definitely. I’ve looked at Milton Keynes and of course that environment is completely different to somewhere like London and yet it still produced artists such as Foul Play and TCM.

Owen: Yeah exactly. I mean some of it was obviously Hackney, ‘Shut up and Dance’ and the people around them were extremely Hackney. And you had 4Hero and the Reinforced lot that were very West London, Acton to Dollis Hill way. Suburban but industrial. But yeah I mean loads of it was people from Essex, Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire. So I think that really should be stressed. And whats interesting about those sorts of places, if you aren’t into architecture, is their combination of both boredom and mobility. They would generally be found in those new town environments. Milton Keynes and Stevenage can be seen as being quite boring when you are 20 years old. But of course because of the way they were planned with the road systems first and everything second, they were incredibly easy to get out of and into. They were full of spaces where you could put on raves. And that experience of driving around is also part of it. I don’t think young people now drive as much. Jungle and Hardcore seemed to me to be car music. They were made by and for people who drive cars. And that is a very suburban experience. And again that isn’t the whole story, but another facet. The East London, Hackney scene etc was still incredibly important to Jungle and was separate from that. Maybe the kind of Ragga Jungle scene can be bracketed off from Moving Shadow as more Hackney based.

Me: Do you feel as if the darker, futuristic sort of Jungle was more city or suburban based?

Owen: I mean that West London scene [4hero] was incredibly futuristic, as futuristic as anything moving Shadow were doing. Its tough to say. The stuff that is on the cusp of Jungle, that really revolutionary stuff, is coming from reinforced records. I mean also a lot of the rudeboi ragga stuff comes from the suburbs too. I mean obviously, suburban base put out loads of ragga jungle. And they aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive. A lot of the stuff that is really for the lads, or is ragga, is also very very futuristic. I don’t think there is a line that can be drawn.

Thank you to Owen for the time and responses

¶¶¶¶¶

¶¶¶¶¶

¶¶¶¶¶

¶¶¶¶¶

¶¶¶¶¶

This forthcoming blog entitled Concrete Jungle aims to collect all my thoughts and writings on Jungle Drum & Bass. It will include histories of particular elements of the music, thoughts on the modern day scene and events, as well as interviews and conversations about the music with individuals apart or outside of the scene.

¶¶¶¶¶

¶¶¶¶¶

¶¶¶¶¶

¶¶¶¶¶

¶¶¶¶¶

Leave a comment